Social Media For Your Sydney Wedding

Introduction

Sydney weddings are some of the most beautiful in the world. The city skyline and the harbor make for a stunning backdrop, and there are plenty of options for venues that will make your wedding day unforgettable. But as with any wedding, planning is key. And one aspect of planning that can’t be overlooked is social media. From promoting your wedding to sharing photos and memories after the big day, social media should be a part of your Sydney wedding plan. In this blog post, we’ll explore some ways to use social media to your advantage before, during, and after your wedding day.

How to Use Social Media to Plan Your Wedding

When it comes to wedding planning, social media is your best friend. There are a ton of great resources out there that can help you plan your dream Sydney wedding, and all of them are just a few clicks away.

Here are some great ways to use social media to plan your Sydney wedding:

1. Follow wedding planners and other industry professionals on Twitter. This is a great way to get insights and tips from the experts, and it’s also a great way to keep up with the latest trends.

2. Use Pinterest to create mood boards for your wedding. This is a great way to get inspiration for your own unique vision.

3. Join wedding-related Facebook groups. There are tons of great groups out there that can offer support, advice, and even vendor recommendations.

4. Use Instagram to find inspiration for everything from your dress to your flowers to your décor. Hashtags are your friend here!

5. Be sure to follow Sydney Wedding Company on all our social media channels! We share lots of helpful tips and information on our blog and across our social media platforms, so be sure to stay connected with us for all the latest news and updates.

Tips for Using Social Media for Your Wedding

When it comes to social media for your wedding, there are a few things to keep in mind. First and foremost, you want to make sure that you are using social media to connect with your guests and not just to promote your wedding. Secondly, you want to be sure that you are using social media in a way that is respectful of your guests’ privacy. Lastly, you want to make sure that you are using social media to create lasting memories of your wedding day.

Here are a few tips for using social media for your wedding:

1) Use social media to connect with your guests: Be sure to post updates about your wedding on your social media channels and encourage your guests to interact with you online. This is a great way to get everyone excited about your big day!

2) Use it in a respectful way: Remember that not everyone wants their wedding photos plastered all over the internet. Be considerate of your guests’ privacy when it comes to posting photos and updates about the wedding on social media.

3) Use it to create lasting memories: Share photos and updates from your wedding day on social media so that friends and family who couldn’t be there can still feel like they are part of the celebration. You can also use social media to create a virtual scrapbook of sorts by compiling all of the photos and posts from your big day in one place.

The Benefits of Using Social Media for Your Wedding

As a Sydney Wedding Photographer, I often get asked by couples whether they should use social media for their wedding. While there are pros and cons to everything in life, I believe the benefits of using social media for your wedding definitely outweigh the negatives.

Benefit #1 – You Can Reach More People

With over 2 billion active users on Facebook alone, chances are you’re going to be able to reach more people by sharing your wedding photos and updates on social media than you would if you kept them private. This is especially beneficial if you have family and friends who live far away and can’t make it to your wedding in person.

Benefit #2 – It’s Free Marketing

If you’re a business owner, you know the importance of marketing. By sharing photos and updates from your wedding on social media, you’re effectively doing free marketing for your business. If people see how beautiful your photos are and how much fun you had at your wedding, they’re more likely to book you for their own event.

Benefit #3 – You Can Connect With Other Couples

There are tons of active wedding-related communities on social media where you can connect with other couples who are planning their weddings or who have just gotten married. These communities can be a great resource for advice, support, and even deals on vendors.

The Different Types of Social Media Accounts to Use for Your Wedding

As you begin planning your Sydney wedding, you will quickly realize that there are a multitude of social media accounts to choose from. While it may seem overwhelming at first, we promise that it is not as complicated as it seems! To help you navigate the social media world, we have compiled a list of the different types of accounts to use for your wedding.

1. Facebook – This is one of the most popular social media platforms and can be used to share updates, photos, and videos with your friends and family. You can also create a private group for your wedding guests to stay up-to-date on all the latest news.

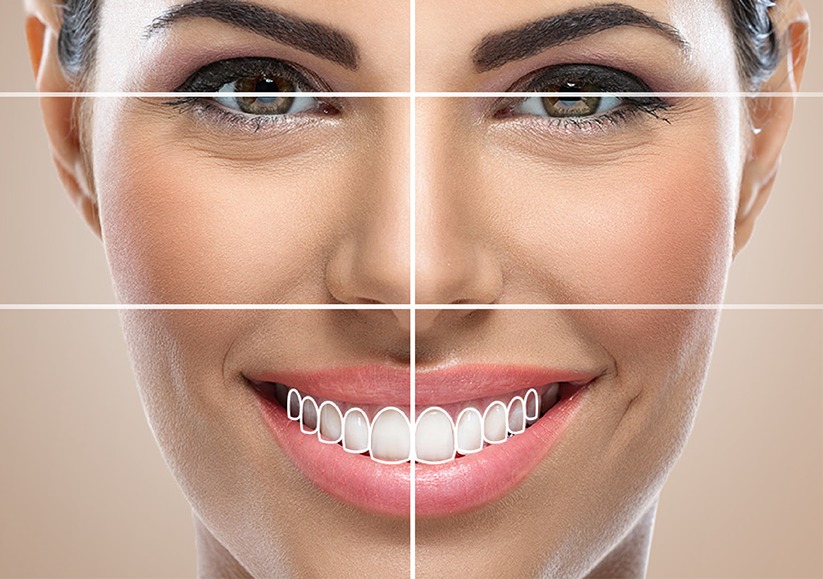

2. Instagram – This visual platform is perfect for sharing beautiful photos of you and your partner, as well as sneak peeks of your wedding preparations. Be sure to use relevant hashtags so that your photos can be easily found by other users.

3. Twitter – This microblogging site is great for sharing quick updates about your wedding planning process or for live-tweeting during your big day! Use hashtags to reach a wider audience and connect with other users who are interested in weddings.

4. Snapchat – This app is perfect for sharing fun moments leading up to your wedding day. Snapchats disappear after 24 hours, so they are perfect for sharing candid shots that you may not want saved forever. Plus, your guests will love getting snaps from you on such a special occasion!

5. Tiktok – One of the latest and popular social media platform. Users can record and share videos with friends and others. It’s a popular app amongst younger audiences as an outlet to express themselves through singing, dancing, comedy, and lip syncing.

What to Post on Social Media for Your Wedding

When it comes to social media and your wedding, there are a few things you will want to keep in mind. First and foremost, you will want to make sure that you are only sharing information that you are comfortable with everyone knowing. This means that if you have any details about your wedding that you would prefer to keep private, then you should refrain from posting them on social media.

In addition, you will want to be mindful of the tone of your posts. Remember that this is a happy occasion, so try to keep your posts positive and upbeat. Also, avoid using social media as a platform for venting about any stressful wedding-related matters; no one wants to read about that!

Finally, think about what kind of content will be most interesting to your friends and family members. Of course you’ll want to share some photos from the big day, but also consider posting other fun things like a sneak peek of your dress or suit, or a video of your first dance. Whatever you decide to post, just make sure it’s something that will make your loved ones smile.

How to Get More Followers for Your Wedding Hashtag

If you’re looking to get more followers for your wedding hashtag, there are a few things you can do. First, make sure your hashtag is easy to remember and spell. Second, use it consistently across all your wedding-related social media platforms. And third, post engaging content that will encourage people to follow you.

Here are some tips for each of these:

Make sure your hashtag is easy to remember and spell: Choose a short and sweet hashtag that’s easy for people to remember and spell. This way, they’ll be more likely to use it when sharing photos and videos from your wedding.

Use it consistently across all your wedding-related social media platforms: Use your hashtag on all your wedding-related social media accounts, such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and Snapchat. This will help people easily find your content when searching for your wedding online.

Post engaging content that will encourage people to follow you: Share photos and videos of your wedding preparations, the big day itself, and any post-wedding festivities. Also be sure to share any behind-the-scenes content, such as photos of you getting ready or candid shots of you and your spouse during the reception.

Tips for Using Social Media for Your Wedding

Planning a wedding can be a daunting task, but there are many resources available to help you. Social media is one of the most powerful tools you can use to plan your wedding. Here are some tips for using social media to your advantage:

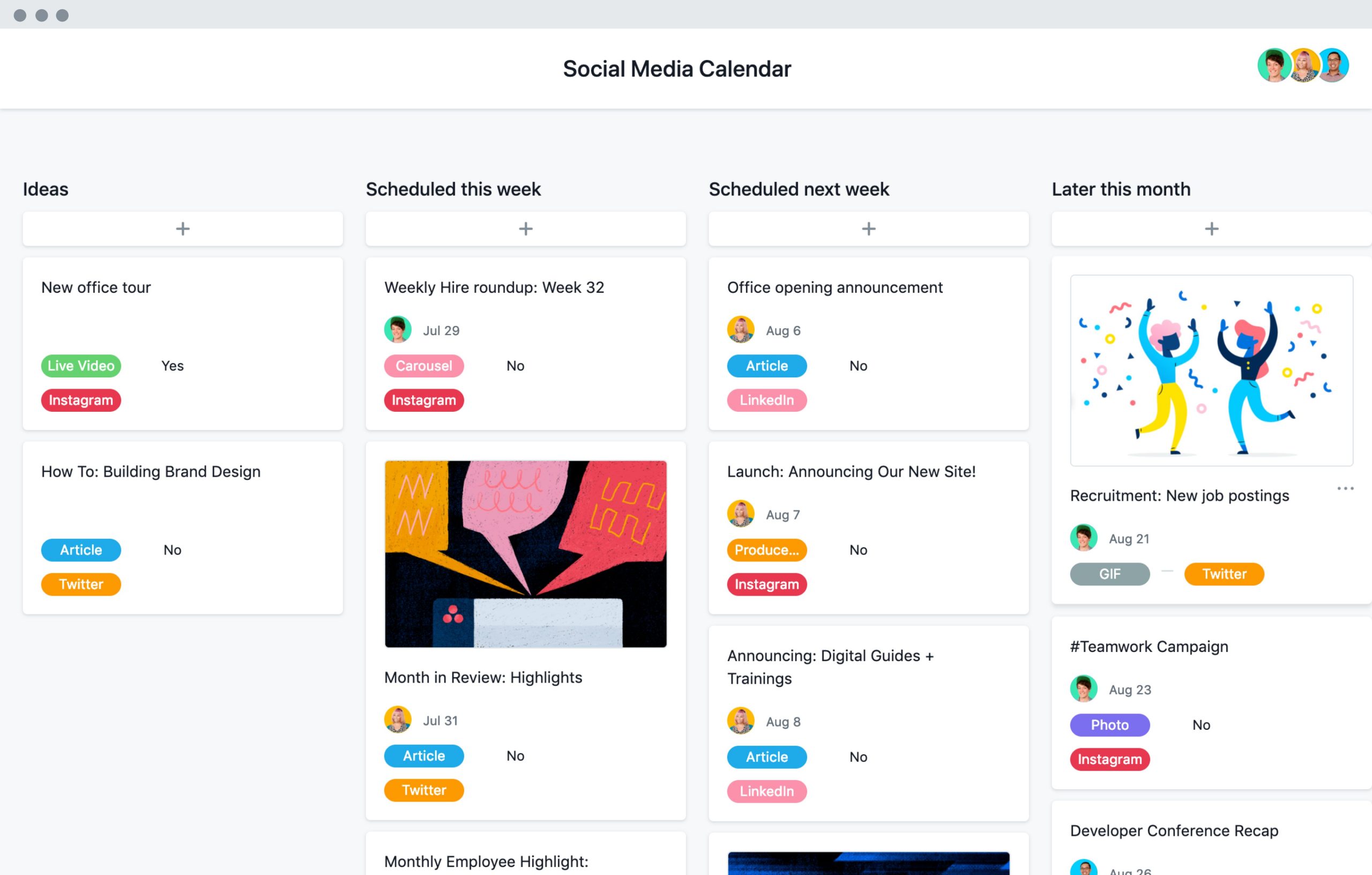

1. Start by creating a wedding website or blog. This will be your central hub for all things wedding-related. Be sure to include key details like your wedding date, location, and contact information.

2. Use social media to share updates and communicate with your guests. Create a hashtag for your wedding and encourage guests to use it when posting photos and updates.

3. Utilize social media tools like Facebook Events and Pinterest to help with the planning process. Facebook Events is a great way to keep track of important deadlines and RSVPs, while Pinterest is perfect for inspiration boards and finding vendors.

4. Get creative with your content! In addition to traditional posts, try using video and live streaming to give your guests a behind-the-scenes look at the planning process (and maybe even the big day itself!).

5. Don’t forget about post-wedding content. Use social media to thank your guests for their support and share photos from the big day. You can also use it as a platform to continue sharing memories from your honeymoon or first year of marriage.

How to Create a Hashtag For Your Wedding

If you’re looking to use social media to help promote your Sydney wedding, one of the best ways to do so is by creating a hashtag for your event. This will allow all of your guests to easily follow along with everything that’s going on, and will also make it easy for you to look back and see all of the great memories from your big day.

To get started, come up with a unique hashtag for your wedding. This can be something as simple as your names or the date of your wedding. Once you have your hashtag, be sure to promote it far and wide. Include it on your invitations, in any social media posts leading up to the big day, and even on signage at the event itself.

Encourage your guests to use the hashtag when posting about your wedding on their own social media accounts. You can even offer a prize for whoever uses it the most! At the end of the night, you’ll have a beautiful feed full of memories from your special day that you can cherish forever.

Conclusion

There you have it! Our top tips for using social media to promote your Sydney wedding. We hope you found these tips helpful and that you’ll be able to use them to get the word out about your big day. If you have any other questions or would like some help planning your wedding, feel free to contact us. We’d be more than happy to assist you in any way we can!